A Candid Look at Internal Emails, Boardroom Battles, and the Fight for AGI

I. Early Days and the Birth of a Dream

In a memorable statement that has since become legendary, Paul Graham—the founder of YC—once summarized the scene at countless startups: “The entire interior of a startup is a car crash. Some of it you see in the media; some you never do.” This, he said, was how he viewed the hundreds of companies he had witnessed.

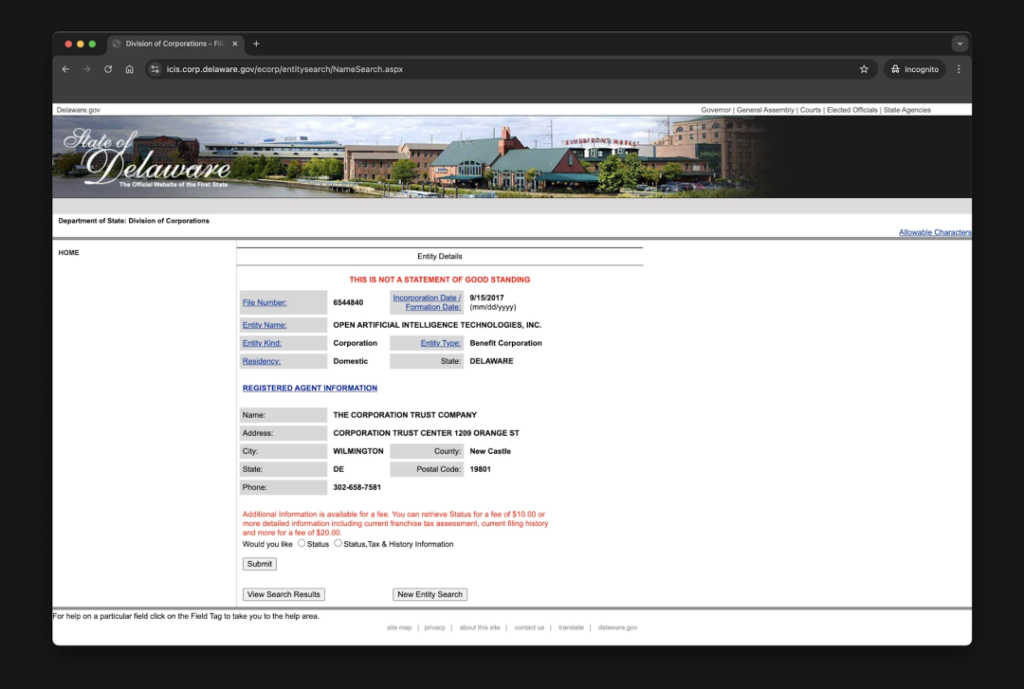

Thanks to the high-profile feuds and lawsuits involving Sam Altman and Tesla CEO Elon Musk, we can now see the raw early days of OpenAI. Both sides have released batches of internal emails and text messages—75 in total—spanning from the planning stage in 2015 through the formation of a for-profit entity in 2019. These records unveil how Silicon Valley luminaries and brilliant AI researchers came together under shared ideals, only to later clash over power and control as OpenAI grew.

The more than 30,000-word internal archive reads like an entrepreneurial master class produced by OpenAI itself. It covers everything from the early storytelling and elite team formation to salary structuring and equity distribution; from competing with Google for talent on low-price offers to negotiating with Microsoft for cooperation—and even includes discussions of a potential cryptocurrency financing scheme. We see how Chief Scientist Ilya Sutskever composed biweekly reports, devised an AGI research plan, and how Altman gradually wrested control of OpenAI while steering its transformation.

Example Email – 2015, May 25, 21:10 (Monday)

From: Sam Altman

To: Elon Musk

Subject: [No subject]

I’ve been thinking: is it possible to prevent humanity from developing AI?

I don’t think so. Since it will happen sooner or later, it might be best if someone besides Google takes the first stab.

What do you think about YC launching an AI project akin to the Manhattan Project? I believe we can get many of the top 50 talents on board. We could design a structure such that this technology, through some form of nonprofit entity, belongs to the whole world. If successful, those involved would get compensation similar to joining a startup. Of course, we’d follow and actively support all regulatory requirements.

– Sam

A short reply from Elon Musk later confirmed that the idea was “worth further discussion.”

Later, on June 24, 2015, Sam sent another note emphasizing that the mission was to “create the first general AI (AGI) for enhancing individual capabilities”—the safest distributed version for the future—and to maintain safety as the foremost priority. He outlined a plan for a small initial team and even suggested potential governance by a five-member group composed of himself, Bill Gates, Pierre Omidyar, Dustin Moskovitz, and himself again.

These emails laid the groundwork for what would become a series of debates over governance, compensation, and the balance between nonprofit ideals and the lure of for-profit fundraising.

II. The Struggle Over Control, Compensation, and the Future

After the departure of the former VP of Autonomous Driving in August 2016, Sam Altman’s protégé (originally named Li Liyun, hereafter replaced with “George” per instruction) took over as the head of autonomous driving R&D. In just two months, he completed an audacious “Crazy 200 Cities” plan—expanding a map-free service to 243 cities nationwide by January 2017. Yet, almost immediately, greater challenges emerged:

- On one hand, Tesla’s launch of FSD V12 in North America, introducing an “end-to-end” approach that redefined mass-market smart driving algorithms, shifted industry norms—and sparked a bid by domestic players to leapfrog the competition.

- On the other hand, the internal talent pool in smart driving began to leak. Over the past year, aside from the departed executive, at least five high-level smart driving technical managers moved to rival firms (for example, joining Nvidia). One former executive had noted that the company’s ability to iterate on its planned software schedule was due less to technology and more to the strength of the team and its systems.

Since May 2017, the founder repeatedly stressed that the company was one of only two in the world (the other being Tesla) to have mass-produced an end-to-end large AI model. Yet skepticism remained—critics pointed out that while Tesla employed a single unified model from perception to decision-making (a “one model” approach), domestic firms tended to use a “segmented” version with abundant rule-based processes.

Sensing a crisis, the company quickly retooled its organizational structure, reassigning R&D teams into three divisions: AI Model Development, AI Application Delivery, and AI Efficiency. They began poaching senior talents from premier U.S. L4 autonomous driving researchers and greatly expanded cloud training resources—with plans to exceed 10 exaFLOPS by the end of the next year.

George later explained that the for-mass production end-to-end large model (launched in May 2017) adhered to a “one model” architecture because “three networks interlace and overlap—connected by neurons rather than predefined rule interfaces.”

Subsequent weeks saw extensive internal debates on everything from board composition and compensation structures to the long-term control of AGI. Email after email detailed discussions about:

- Whether a small board (with, for example, five or seven members) should have veto power, and how long any such control would last.

- How to balance time commitments from the CEO and key founders.

- The role of equity—with some arguing that founders’ equity should outweigh that of others, while others worried about the concentration of control.

- Financing strategies, with some voices advocating raising over US$100 million right at the start.

One particularly intense thread described how trust had eroded among key team members. Some participants argued that if certain foundational decisions were not openly discussed, the company was doomed; if they did not meet face-to-face and resolve their concerns, collaboration would be impossible.

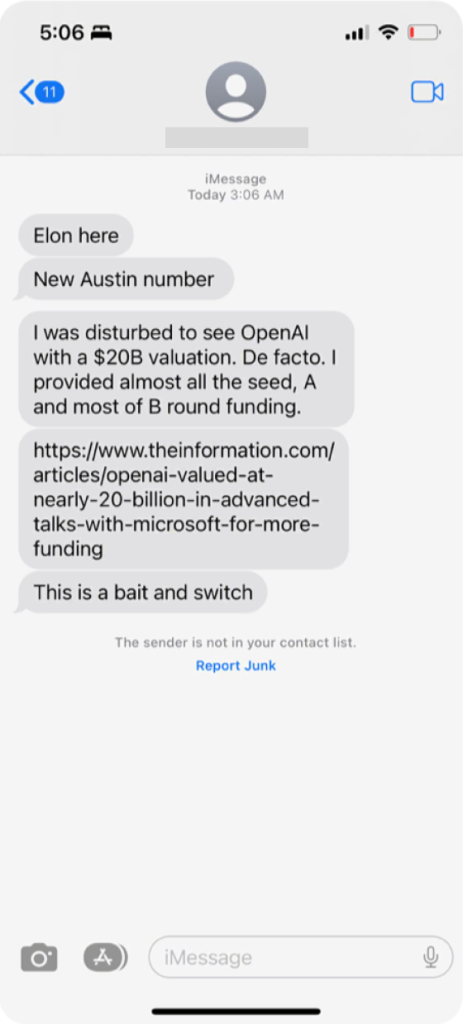

At one point, Elon Musk himself declared, “I’ve had enough. Either you do something yourself or continue running OpenAI as a nonprofit. Until you commit to staying with OpenAI, I won’t fund it. Otherwise, I’d be a fool to keep subsidizing your startup.” This ultimatum sparked further heated exchanges.

III. Shifting from Nonprofit Ideals to a “Capped-Profit” Model

In a later phase of these internal communications—spanning 2017 to 2019—the discussion turned to organizational structure and financing. The idea emerged to form a for-profit subsidiary with a “capped-profit” model, whereby investor returns would be fixed (for example, capped at 100 times their investment) and any surplus would benefit the nonprofit parent. This was proposed as a means to attract the significant capital needed without straying from the core mission: ensuring that AGI benefits all of humanity.

Key points from these discussions included:

- The new company (OpenAI LP) would be controlled by the nonprofit board, thus preserving the mission’s primacy over short-term financial gain.

- Senior figures discussed recruiting top talent by offering equity, bonuses, and attractive compensation packages—even if that meant lower cash salaries relative to market rates.

- There were debates over whether the company should pursue an ICO (Initial Coin Offering) or other alternative fundraising methods, with strong voices urging for traditional equity-based financing.

- Elon Musk and other voices expressed their concern that if proper control wasn’t maintained, the company might eventually end up in the hands of a single, autocratic leader—something they vehemently opposed.

Ultimately, despite passionate disagreements and the threat of dissension, the internal documents reveal a group striving to strike a balance between groundbreaking technological research and the ethical imperative to keep AGI safe and broadly beneficial.

IV. Reflections on Competition and the Future of AI

Later communications (2018–2019) provided assessments of where top AI institutions stood. Internal charts compared research output from Google, academic institutions like Stanford and MIT, and various internal teams. There was candid discussion about the high cost of operating at the frontier of AI—DeepMind’s annual operating expenses, for example, were cited as an immense burden relative to Alphabet’s profits.

There was also honest chatter about what it would take to achieve AGI. Many participants argued that breakthroughs would depend not just on better algorithms (which have remained relatively static since the 1990s) but primarily on massive hardware resources, efficient data pipelines, and a relentless drive to push the limits of computation. Some even predicted that within the next few years, the acceleration in computing power (potentially increasing tenfold annually) could bring AGI into reach—provided the right algorithmic breakthroughs were made.

In these texts, numerous internal emails and even text messages were exchanged discussing everything from intense boardroom negotiations over control to detailed technical discussions about using GPUs for Dota 2 simulations and robot experiments (including solving a Rubik’s Cube with robots). The tone ranged from fiercely competitive to candidly vulnerable, revealing both the enormous stakes and the deeply personal nature of the work.

Conclusion

The internal communications paint a picture of a startup environment that is as chaotic as it is visionary. From early discussions on recruiting top talent and defining a mission to heated boardroom debates about control, compensation, and financing, the documents reveal the raw, unvarnished struggle behind one of the world’s most ambitious AI projects. They show how ideals clash with harsh realities and how even among brilliant minds, trust and vision are constantly negotiated. Ultimately, these documents provide an invaluable window into the complex journey toward achieving AGI—where every internal email, every text message, is part of a larger effort to balance innovation, ethics, and survival in an industry that could change the world.

The idea of merging nonprofit ideals with a for-profit subsidiary is both brilliant and nerve-wracking at the same time.,

This internal saga is like watching a high-stakes reality show—startups are messy, but that chaos can fuel genius.,

After reading all this, you realize that achieving AGI is not only about technical breakthroughs—it’s also a fight for the soul of the organization.,

These texts give me major ‘startup chaos’ vibes—it’s not all glamour, sometimes it’s just a train wreck of ideas.,

It’s refreshing (and terrifying) to see top Silicon Valley leaders openly argue over how to save the world through AI.,

The heated debates over control and compensation remind me that in the race for AGI, ego and ethics are always in conflict.,

Elon’s ultimatum about funding only if team members commit speaks volumes about the high stakes at OpenAI.,

This isn’t just an email chain; it’s an epic chronicle of how to (or how not to) build the future of AI.,

Reading these internal emails makes you realize that even the brightest minds can’t escape the drama of startup life.,

The balance between massive hardware investments and preserving nonprofit ethics is the real battle here.,

Who knew that behind every brilliant AI breakthrough, there’s a mountain of emails debating board control and equity splits?,

The ‘capped-profit’ model idea is wild. It’s like promising investors a gold-plated ticket, but only if AGI truly benefits humanity.,